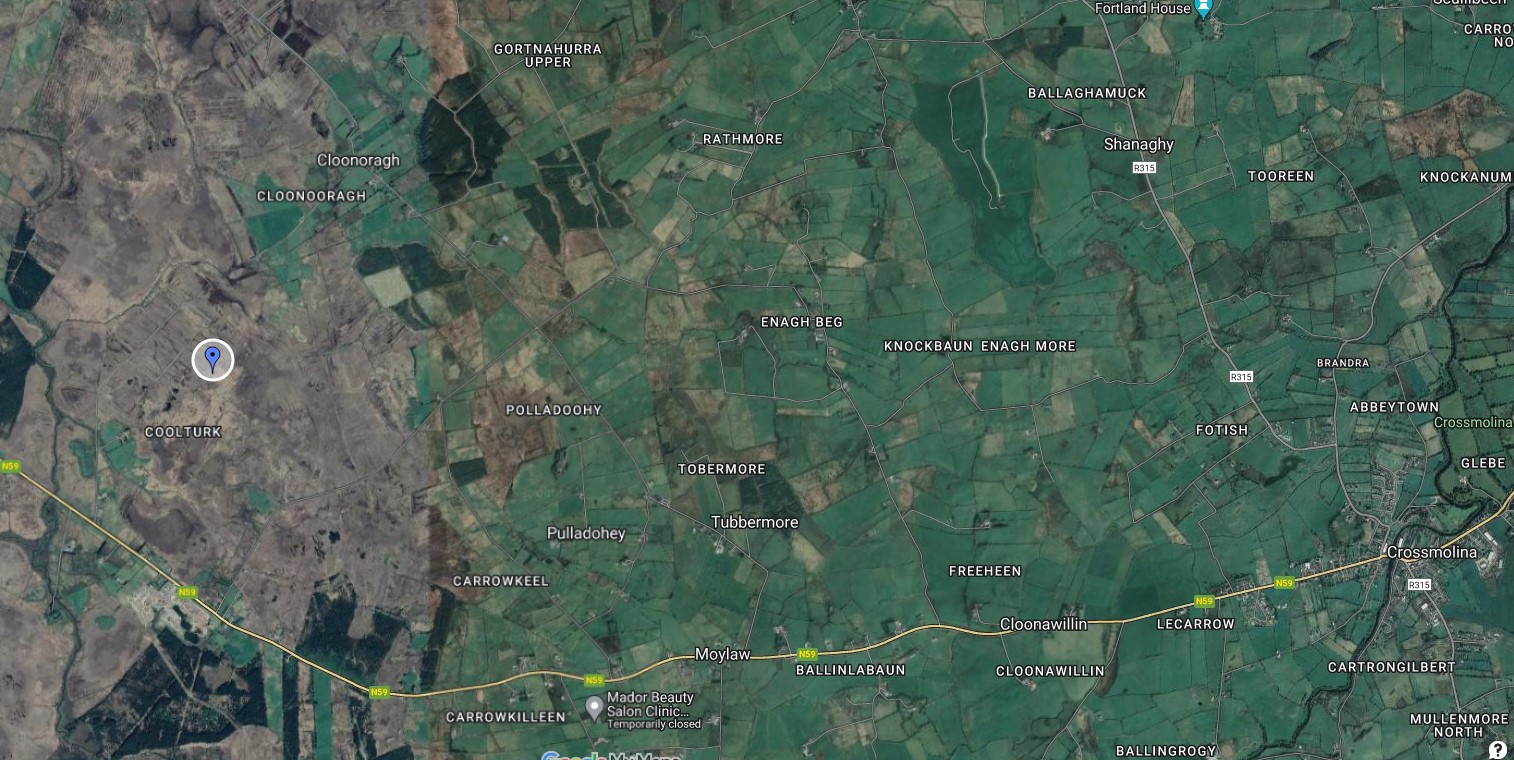

Douglas Boston BZ200, Coolturk, Crossmolina, Mayo

On the 25th of October 1942, a small twin engine light bomber from the Royal Air Force attempted to make a forced landing near Crossmolina, County Mayo. The pilot, thinking he was landing on solid ground, unfortunately was landing on a peat bog, a soggy wet mass. In the resulting landing attempt, the aircraft, a Douglas Boston bomber, cartwheeled over onto its back. The navigator and radio operator/air gunner were able to escape but the pilot, Nils Rasmussen, a Norwegian, was not so lucky. He was killed in his cockpit. The location was described in the Irish Army report as approximately "four and a half miles from Crossmolina on the Belmullet road, the 500 yards down a lane to the N. of the road (this is the nearest point to which a truck can be brought), and from thence another 500 to 600 yards over a swamp or moving bog to the plane." This is described as belonging to John Callaghan, Coolturk. Coolturk and Pulladoohy are adjacent townlands. The location of the crash was advised by local man Sean Syron as shown below.

This photo of Boston

BZ200 is found in Donal McCarron's book, "Landfall Ireland" and

in two Mayo local history journal article by a Seamus

Callaghan. I am interested to get a better quality copy of

the image.

This photo of Boston

BZ200 is found in Donal McCarron's book, "Landfall Ireland" and

in two Mayo local history journal article by a Seamus

Callaghan. I am interested to get a better quality copy of

the image.

One can see the main landing gear wheels at the top of the

image, the engines ahead of them, and the missing nose landing

gear which had caused the aircraft to somersault when it dug

into the boggy ground. There is a large fuel tank pod on

the belly of the aircraft.

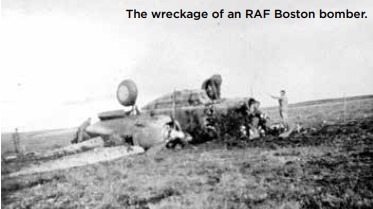

Another photo, taken from a different angle appeared in a 2017

article by researcher Tony Kearns, possibly attributed to the

Irish Air Corps museum,

The aircraft was an American built, Douglas Boston IIIA light

bomber. This airframe was built under its US Army Air Forces

designation of A20C-1-DO, indicating its being part of the first

production batch of the A20C variant built by Douglas. Upon

delivery to the RAF in Canada, it became a Douglas Boston IIIA.

It was part of a batch of about 200 Boston IIIA's to serve with

the RAF and they saw much action in the years 1942/43. It is

interesting to look at the ten airframes in the serial batch

BZ200 to BZ209. BZ202, went missing on a mission in autumn 1944;

BZ203, Shot down in France in Oct 1943; BZ204, Crashed in

England Mar 1944; BZ205, Crashed in England 1945; BZ207, Missing

on a mission off Italy, April 1944, BZ209, crashed on its Ferry

flight October 20th, 1942. Seven out of the ten met with a bad

end. The details come from Joe

Baugher's website on US military serial numbers.

The Irish Army at the time concluded that the bog was so

dangerous, it was not worth the risk attempting to salvage the

aircraft and it was left to John Callaghan. The days after

the Army guard left, industrious locals dismantled what they

could with the engines sinking into the bog. Pieces of the

aircraft could be found in gaps and farms for years after.

The surviving crew of the aircraft were taken in hand by

members of the Local Defence Force (LDF) and later by the Irish

Army. The two survivors were:

Sgt Peter Frank CRASKE 1387671, Royal Air Force.

F/Sgt Frederick Michael FULLER R/92107, Royal Canadian Air Force

|

|

|

|

Nils Bjorn RASMUSSEN, Pilot |

Peter Frank CRASKE, Navigator |

Frederick Michael FULLER, Wireless Operator/Air Gunner (WAG) |

The Irish Army reports on the crash are not extensive. The Army

reported as normal that a detachment was sent to the crash site

and the survivors were looked after. This detachments officers

reported that the survivors were uninjured. The two airmen were

sent across the border to Northern Ireland shortly after the

crash.

The aircraft had ended up upside down in the bog, trapping KVM

Rasmussen in the cockpit. The fuselage had to be cut by the

military guard to extract his remains. The nature of the bog was

such that the military deemed any salvage operation to be

impractical. The local people however took less heed of this and

the remains of BZ200 were cut up and dismantled over the

following few days. Seamus Callaghan, a local man, wrote in 1992

that even young people in the area to that day knew of the crash

as there were parts of the aircraft used as gates all over the

community for many years after

Local man Sean Syron (at left) provided this image of himself

with Seamus Callaghan (at right), author of the local history

articles on the crash and in the middle, Thomas Leonard, a

wartime witness of the plane crash. In the background,

Nephin Mountain rises in the distance.

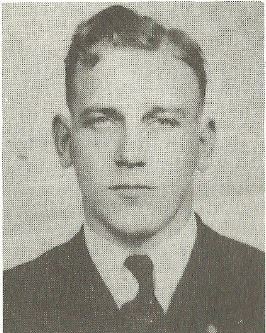

Peter Craske

came from London and was aged 20 at the time of the crash. He

remained in North America after the war and was contacted in

2009 and very kindly shared his memories. Peter emailed in 2009

the details of the trip that he had recorded in his flying log

book.

Peter Craske

came from London and was aged 20 at the time of the crash. He

remained in North America after the war and was contacted in

2009 and very kindly shared his memories. Peter emailed in 2009

the details of the trip that he had recorded in his flying log

book.

We left Montreal (Dorval) at 1505 GMT

on October 16th 1942 and flew to Gander, Newfoundland.

Flying time was five hours and two minutes.

We had a layover in Gander waiting for good weather until

October 25th. This was a relatively long period and would

have been due to the limitations placed on a short range

aircraft, such as the Boston, attempting the direct flight

across the Atlantic.

On the 15th, we took off at 0605 GMT and flew for 11 hours

and 20 minutes before coming down in Ireland. Of that

period, two hours were recorded as night flying and 9.20 as

day.

Peter returned to Canada after this

flight was married only a few weeks after his crash in

Ireland. He wrote of his ferrying activities in the early

months of 1943:

At that time I was flying the South Atlantic route, mostly

on A30 Baltimore attack bombers being used in the North

African campaign against Rommel. To get them to Africa,

because of their limited range, we had to fly short legs

Nassau - Porto Rico - Trinidad - British, French and Dutch

Guiana - Belem - Recife, Brazil - Ascension Island - Accra

on what was then the African Gold Coast. We lost quite a few

crews on that run because the A30, when fitted with overload

tanks that protruded through the bomb bay with only a few

inches clearance from the ground, made the aircraft very

tricky to handle on take-off. Many would swing and ground

loop, collapsing the undercarriage on to the overload tank -

with predictable results. I can assure you that these were

not stress-free flights!

Peter provided a detailed recollection of the flight and crash.

He was particularly amused by the Irish Army recording that he

was not injured; he had been badly cut during the crash. Peter's

story is at the bottom of this page, click here

to view it or scroll down. After serving with Ferry Command up

to January 1944, Peter was posted to the RAF in England and

appears in the Operations Record Book of 512 Squadron, Transport

Command on the 18 February 1944, a unit which was flying the

Douglas Skytrain transport. At the time of the Normandy

landings he had been flying three months of airborne exercises

across the UK. He flew into France on the night of June 5th,

1944 under Harold Chatfield, his crew dropping 17 paratroopers

near Ouistreham. Four months later he was in the air over

Holland in support of the attack on the bridge at Arnhem.

Following the German capitulation he was transferred to 48

Squadron and served in Burma and Malaya before being demobilized

in September 1946.

Peter passed away on 19th December 2019 in Ottawa.

The pilot, Nils Bjørn Rasmussen was laid to rest in the rural cemetery in Kilmurray near Crossmolina on October 27th with military honours. His headstone is a Norwegian War Grave pattern headstone. Pedar Rasmussen from Risør in Norway is a relative of Nils. He remembers Nils visiting his father when he was a young lad. Pedar provided the following background on Nils.

Nils B Rasmussen was born in Risør, Son of

Carl Hjalmar Rasmussen died at sea 9.9.1918, and Berte F.

Nilsen, born 1889 in Dypvåg, - died 1920. Carl was my

father's older brother. Nils Bjørn Rasmussen, was born 2.

August 1917 in Skolegata in Risør.

Nils B Rasmussen was born in Risør, Son of

Carl Hjalmar Rasmussen died at sea 9.9.1918, and Berte F.

Nilsen, born 1889 in Dypvåg, - died 1920. Carl was my

father's older brother. Nils Bjørn Rasmussen, was born 2.

August 1917 in Skolegata in Risør.

Nils Bjørn went to Middelschool (3 year after the 7 years public school) and then a mechanic technical college for 2 years, and then air force recruit school. He was a seaman when the war started 9. April 1940 and he joined the air force from 1940, here he was educated as pilot in Little Norway, the Norwegian training base in Canada. He served in The Ferry Command. A part of the Air Force flying aircraft and other things from USA to England.

I remember Nils Bjørn coming over the

hills from Gjeving where he lived when I was a kid (I was

about 6-7 years - 1937-38) - he came to visit my father –

his uncle Andreas – on a motor cycle. – My father had a

small engineering workshop in the basement of our house in

Trekta, Risør, (it`s still there). – They both were

“meching” on the motor cycle. – Nils Bjørns mother was born

in Gjeving – and when uncle Carl died in 1918 – she took her

two children; Helena and Nils Bjørn back to her hometown” to

live there.

A local man from the village of Gjeving where Nils grew up sent this photo explaining its background.

The picture I have included shows all

the school children in 1929 or 1930. Nils Bjørn is second

from right in the rearmost row (row with seven boys). To the

right of Nils Bjørn is Stian Hansen who died as a sailor

after being bombed by German planes in March 1940.

Approximately half of the boys in the picture were sailors

during WW2. So was my father as well (in the middle of the

rearmost row). He survived six and a half years of

continuous sailing on a tanker from June 1939 to December

1945, and died in 2011 at an age of nearly 94. Helena

Rasmussen (Nils Bjørn's only sister) is the tall girl with

braids in front of the two teachers to the right.

The Norwegian Training base at Muskoka, Ontario was known as Little Norway. The airport now has a memorial website. Nils Rasmussen has an archived Ferry Command card at the DHD in Canada. It shows that he had ferried five aircraft during 1942, four Lockheed Hudson's, a PBY Catalina and Boston BZ200 was his sixth delivery. After most of these flights his return to Canada was by aircraft, flying on Liberator transports.

The grave of Nils Bjorn Rasmussen in County Mayo.

|

|

The

third man on the aircraft was Frederick Michael Fuller,

a 22 year old from Vancouver, British Columbia. Flight Sergeant

Fuller was a qualified Wireless Operator Air Gunner, normally

shortened to WO/AG or WOP/AG. Frederick joined the Royal

Canadian Air Force in February 1941. He trained at 3 Air

Observers School and then at 8 Bombing and Gunnery School. The

former was based at Regina, Saskatchewan and the latter at

Lethbridge, Alberta.

The

third man on the aircraft was Frederick Michael Fuller,

a 22 year old from Vancouver, British Columbia. Flight Sergeant

Fuller was a qualified Wireless Operator Air Gunner, normally

shortened to WO/AG or WOP/AG. Frederick joined the Royal

Canadian Air Force in February 1941. He trained at 3 Air

Observers School and then at 8 Bombing and Gunnery School. The

former was based at Regina, Saskatchewan and the latter at

Lethbridge, Alberta.

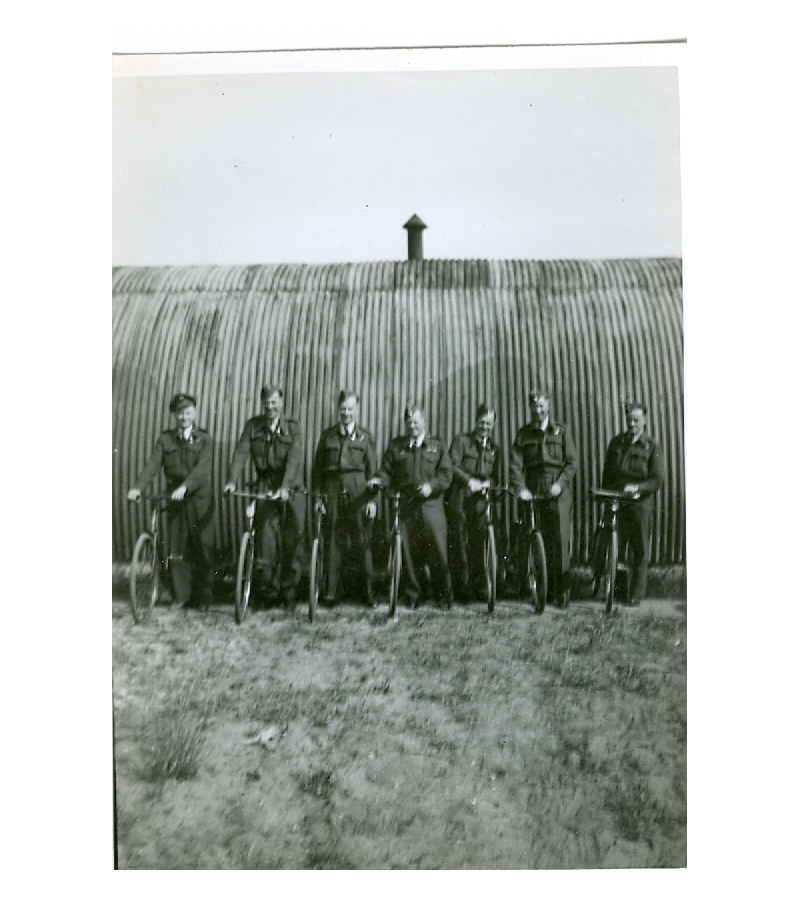

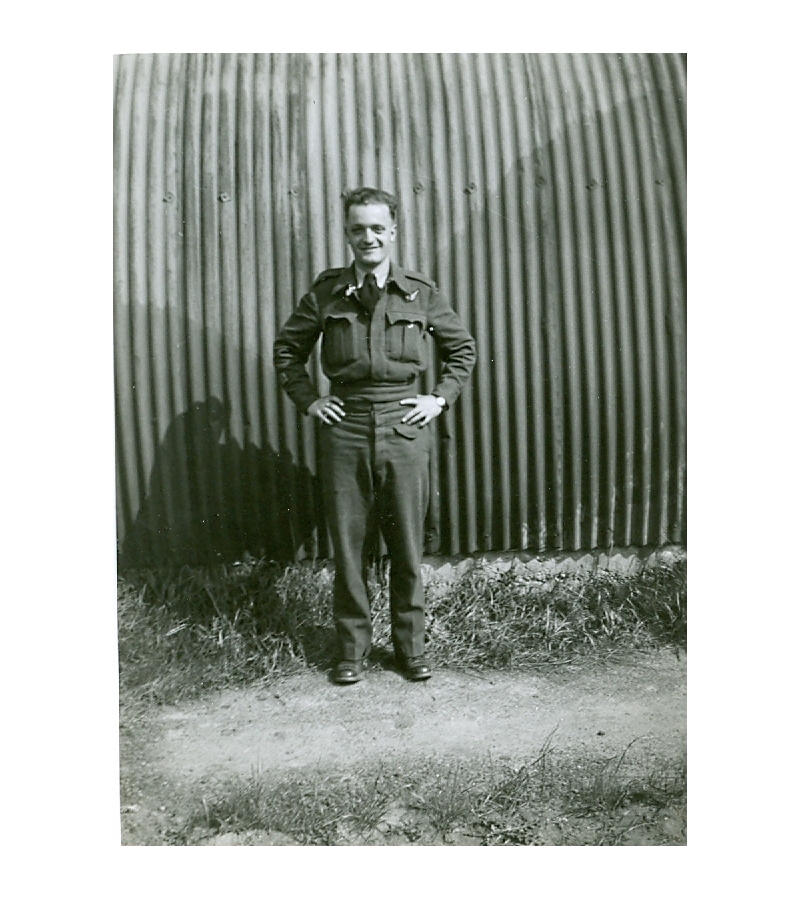

He was then posted to 31 OTU at Debert, Nova Scotia, which was tasked with introducing newly trained aircrew for the task of ferrying aircraft across the oceans. Some freshly trained crew would have traveled direct to their war zones by surface transport; some were chosen to fly one or more Ferry trips. This posting was in March 1942; his postings for the next 19 months were with RAF 45 Group, Ferry Command. His first ferry flight was in June 1942 on Ventura AJ169. His next flight was the ill-fated BZ200 flight. Frederick's service record indicates that he received cuts and bruises in the crash, similar to those that Peter Craske describes. He was admitted to hospital until the 5 November at Lough Erne before returning to Canada as a passenger in Liberator AL592 of the Return Ferry Service. He was given four weeks sick leave and then deemed suitable to return to flying operations. Throughout 1943, he flew on a succession of Baltimore, Boston and Mitchell bombers along with a solitary Catalina flying boat. The Martin Baltimore flights had taken Sgt Fuller to the Middle East, via Nassau and Miami.

Frederick's last Ferry Command flight was in October 1943 when he was crewed up on a Mitchell Bomber. After his arrival in England he was posted to 2 (Observers) Advanced Flying Unit for acclimatization to European conditions. He was then posted in late December 1943 to 82 Operational Training Unit where he presumably met with the crew he flew with when posted to 420 Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force in May 1944.

His crew during his time with 420 Squadron consisted of:

Pilot - F/Lt Thomas Edgar Craig AINSLIE C28055 DFC AFC

MiD

Navigator F/O J G Culligan J28844

Air Bomber F/O Reuben Herbert Davidson J28937 DFC CdG

Flight Engineer Sgt C F Gibbs 1895356 (RAF)

Air Gunner F/O F N Shields J13389

Air Gunner F/O W R Middleton J23375

As the year progressed, some of the above places were taken by

other crew members, but the core of the flight crew remained

together. And during this time, most of the missions flown with

F/Lt Ainslie were on a single Halifax, serial number LW575 which

carried famous nose art painted by one of the squadron members,

Floyd Rutledge. Photo can be seen at

this page. Frederick appears to be the third man standing

from the right of the image.

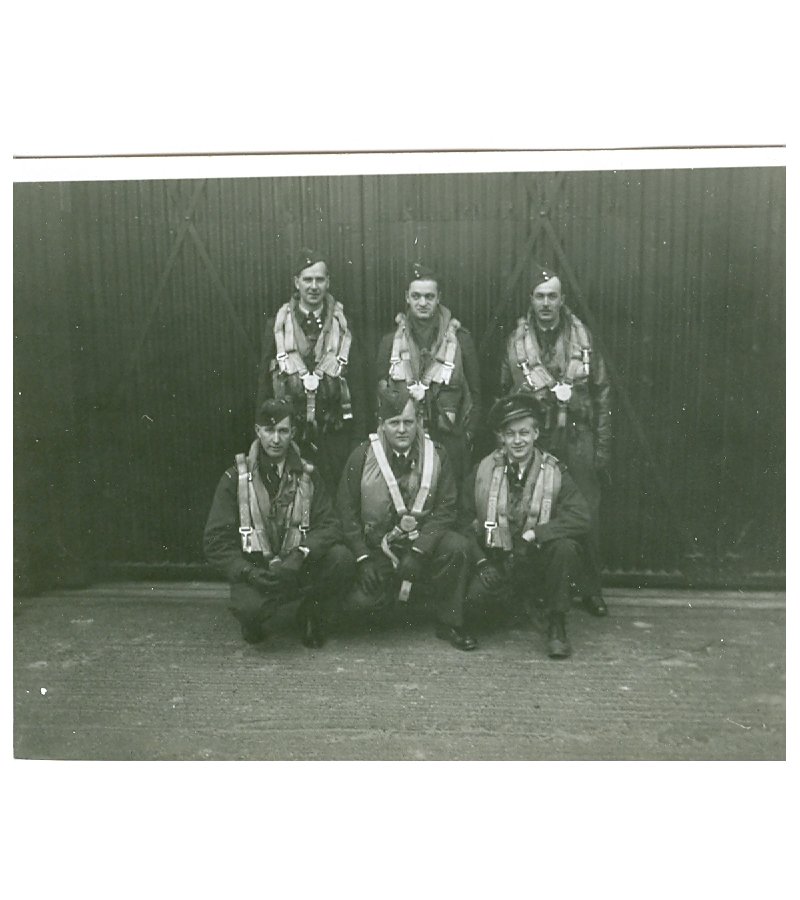

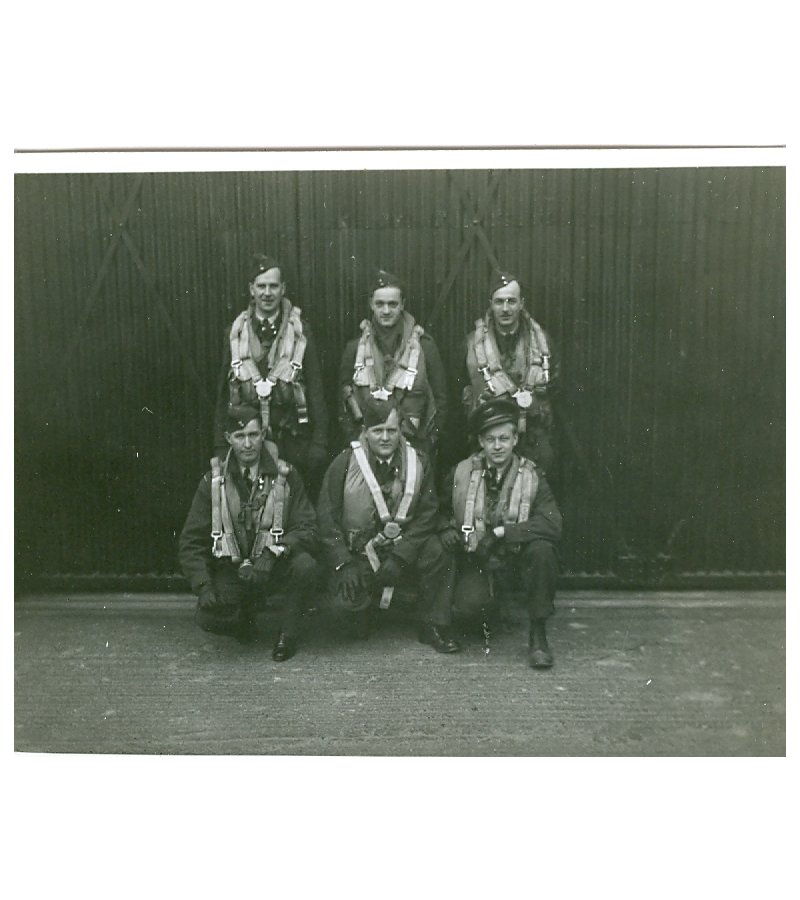

The daughter of his pilot, Craig Ainslie, was so very kind as

to look up her father photos and turned up an amazing collection

of photos containing the young Frederick Fuller, or Mike as he

was known to family.

She was able to provide this large format scan of the crew

standing beneath their aircraft, Pappy's Gang. The crew

members left to right are: 'Lofty', maybe Gibbs?, 'Bert'

Davidson, 'Mid' Middleton, Pilot Craig Ainslie, Mike

Fuller, 'Cully' Culligan, Shields

Click on the numbers below to view the 13 photos from Craig

Ainslie's collection. The family may have additional

photos which Mike Fuller does not appear.

Following his time with 420 Squadron, he was posted back to Canada having served a tour of duty on a front line squadron. During his time with 420 Squadron, Frederick was commissioned as an officer, gaining the new serial number, J89619. In the service record extract that I received for Frederick there is little mention of his time with 420 Squadron but it was taking part in the bomber offensive against Germany at the time.

His service records ends with his planning to return to university in the autumn of 1945 and little more is known about Frederick. He died on the 3rd of August, 1972 in Vancouver, aged just 52. He was single and working as a Longshoreman. His brother in law, Joseph A Hebert was the informant. Frederick's sister Florence was married to Joseph.

Local Mayo man Sean Syron has been a great assistance in passing on information from the local area for this article. He provided these two photos of himself with one witness to the crash, Thomas Leonard and Seamus Callaghan who wrote about the crash in a local history publication.

Peter Craske's recollections of the flight of BZ200 to Ireland

This was my second transatlantic flight with RAF Ferry Command (46 Group) and was in a Boston A20 Aircraft.

The Boston is designated as an Attack Bomber and, as such, has an operational range much less than is required for the longest leg of the Transatlantic crossing from Gander to Prestwick, Scotland. To provide extra fuel capacity, the bomb bay doors of the aircraft were removed, and stowed inside the aircraft allowing the installation of a supplementary fuel tank to be fitted into the bomb bay. This tank in order to be of large enough capacity for the light, extended outside and below the belly of the aircraft, almost dragging on the ground when the undercarriage was down. This resulted in what we termed a “Pregnant Peanut” appearance. As will be seen later, this contributed to the terminal results of the flight.

As a crew, we had not flown together prior to this assignment. This was normal in Ferry Command operations where the availability of the pilots, navigators and radio operators was not sufficient to permit the formation of permanent crews. There was, therefore, a lack of the mutual “team” feeling that usually contributes strongly to a normal, well-established crew.

This, perhaps, needs a bit of explanation.

Ferry Command was not short of pilots – they had been recruited from the then bush pilots and mail pilots in the United States in the early stages of air development which, of course, was the situation in the early 1940’s. There were a few commercial pilots, but very few and these were recruited too. As far as radio operators were concerned, the situation was slightly better. Communications depended on the Morse code, and this was universally used in maritime and land applications. Ferry Command was able to recruit operators from a number of services, albeit with a very wide range of experience, not necessarily related to air operations.

Navigators were an entirely different situation. There were very few available from sea-going operations as such people were indispensable in operating the merchant navy. The minimal number of availabilities from such sources as Imperial Airways and Pan-American who were operating commercial flying boats on long range routes had been utilized to the full. However, the Empire Training Plan was training Observers* in Canada, and the major part of their training was in navigation. (*At that stage of the war, the RAF was still operating under the structure of the Royal Flying Corps as established in WW1 when there were two people in the plane, one to fly and the other to navigate, take photos, drop bombs and fire the machine gun.)

Ferry Command recruited the top graduate navigators from each course and used them to ferry a flight on their return to UK instead of travelling by ship. The success of my first flight had resulted in my being retained by Ferry Command for further flights instead of going to Bomber Command.

Crew's assignments in Montreal made up the crews from the available personnel and assigned them to the flights as they came along.

The process was further complicated by the many different types of aircraft involved. At that stage of the situation, the US was still neutral, and while they could sell the planes, they could not perceived as participating in their delivery. They could ship, but not n US vessels, and this method was severely inhibited by the German U-Boat attacks on merchant ships. So, as aircraft became available and towed across the Canadian border, Ferry Command had to be ready to fly anything and everything to meet the desperate need in Britain.

But not all pilots could fly all aircraft - there are big differences and Crew Assignment had this to take into account among all the others factors.

All of which to explain that the usual interdependent camaraderie and trust, that builds up in a regularly established crew, did not reach a high level in Ferry Command.

So it was that we three, Rasmussen, Fuller and I were assigned to deliver BZ200 to UK, without having previously met.

Prior to leaving Montreal for Gander, Newfoundland , I was told that the aircraft was to be loaded with some aluminum ingots destined for an aircraft factory in UK. A decision had to be made as to where these were to be stowed. They could either be put in the nose “glasshouse” where the navigator usually sits, or in the back where the radio operator works. I elected to have it put in the nose and I would work on the floor in the back where I could communicate with the radio operator in the event that he was able to obtain radio bearings that I could use in my navigation calculations.

Here it should be noted that, in the Boston aircraft, the three crew members were completely separated – Navigator in the nose, Pilot in the cockpit, and radio operator in the rear. Communications between them were rudimentary – a very poor voice communication system backed up by a loop of wire running along the inside of the fuselage. Attached to the wire was a spring clip, and by turning a small crank, messages could be passed from one compartment to another- a very time consuming activity when quick communications and decisions had to be made!

Anyway, I reasoned that I could eliminate a part of that problem by working in the back with Fuller.

The flight to Gander was uneventful, and took about six hours at a speed of about 140mph. (A good speed in those days.) After a layover of a couple of days waiting for some reasonable weather, we took off for Prestwick in the late evening with a flight plan that called for us to arrive at the Irish Coast soon after dawn. I was using astro-navigation techniques similar to those used at sea, depending on a bubble sextant for star sights and position lines. Based on these and my calculations, we crossed the Irish Coast on track and about five minutes off our estimated time – a good result for navigation at that time with none of the electronic aids, VOR’s, Radar or global positioning that aircraft have to-day. Radio aids were confined to QDM’s and similar which were good only for a limited distance from the home station; in this case, crossing the Irish Coast brought us marginally within the range. As we came closer to Prestwick , some bearings were taken which unfortunately, due to poor radio conditions in the aircraft, could not be transmitted back to us. Subsequent to the crash, however, these were plotted and overlaid on my maps and charts, salvaged from the wreckage. They confirmed my calculations.

I gave the captain the course and estimated time of arrival at Prestwick, and we started in that direction. A short while later, as we approached the eastern coast of Ireland , he started to circle as he was under the impression that the water he could see ahead was the North Sea rather than the Irish Sea . I was unable to convince him otherwise. Afterwards he advised that we were getting low on fuel and he was going to make an emergency landing in a green area he could see ahead.

As noted earlier, the bomb-bay tank extending below the fuselage prohibited the possibility of a belly landing.

Fuller and I prepared for a crash landing, wedging ourselves in the corner of the compartment with our flying suits and greatcoats padded around us to try to absorb the impact.

When we touched down, the wheels caught in the bog and the aircraft turned end over end, finishing in the upside down position. In the back we were whipped on to the inside roof of the plane where there were rows of clips used to hold flares. These ripped us quite badly and we were bleeding extensively – but still alive. In desperation for fear of fire, we grabbed hold of the edge of the jammed belly door – now on the top of the upside down plane – and literally peeled it back with our bare hands.

Outside, we were immediately up to our knees in the swamp but somehow managed to get away from the plane in case it went up. We were in rough shape. People came almost immediately, using long poles to get across the boggy land. They took us, separately, to some small huts where women washed us and took care of us.

Later I was taken to the hospital in Castlebar. I can’t remember how we went; at that point I was pretty well out of things and have no recollection of what happened to Fuller. In the middle of the night, I was given civilian clothes, put in a horse and cart and driven for miles through the countryside. Next thing I remember is being in the hospital at Inniskillen. I stayed there a couple of days before being transported to Prestwick.

Many things came together to cause this. The crew situation, the language, the poor internal communications, ditto for the external radio communications that operated only intermittently; the bomb bay tank that prevented a belly landing – all came together.

The only lucky thing from my personal point of view, was my option not to go in the front glasshouse – I wouldn’t be writing to you if I had made the decision the other way!