Lockheed P-38 Lightning, Monaghan, December 1942

Only just over two months separated the first two wartime

aircraft crashes in County Monaghan, one of the counties which

borders Northern Ireland. The first had been on September

29th, 1942, and was the Spitfire which

crashed in Figgular. That crash and this one, were similar

in that the pilots of both aircraft having bailed out, landed

safely within Northern Ireland and thus, never actually arrived

in neutral Ireland. The same could not be said of their

abandoned aircraft.

The Irish Army's Central Control journal records that a message was received at 2052 hours on December 17th, 1942 to the effect that an aircraft had crashed at 1830 hours and completely burned out at Corrintra townland near Castleblaney, County Monaghan. Personnel from the Irish Army in Dundalk were dispatched to the scene. It did mention that a "parachute" and papers were found near the aircraft, which is notable when compared to the statement of the pilot, below. Within minutes, further messages confirmed the pilot had 'made his way to Keady Co. Armagh".

An Irish Air Corps officer Commandant D J Murphy provided a

report to the Army G2 Branch, Military Intelligence, on December

21st and which described events as follows:

The aircraft crashed after dark. According to the

Gardai, a civilian witness of the crash stated that the

Aircraft was on fire before it landed. From the

appearance of the wreckage, this fire must have been very

slight, and was probably exhaust flames. The pilot may

have lost his bearings and abandoned the Aircraft when running

short on petrol.

The report further states that papers found on the wreckage

confirmed that it was an aircraft carrying serial number 'AF

42-12814" and that it was on a delivery or ferry flight.

The aircraft was said to have 'dived almost vertically in a

hard lea field, but not steeply enough to cause it to bury

itself'. The wreckage was therefore strewn about the

field, the guns and cannon were wrecked and most of the

ammunition carried was said to be damaged. The burnt out

parachute found in the wreckage was mentioned but concluded to

have been carried as stowage contents only, since it was early

on known the pilot had bailed out. The location of the

crash was in a field owned by a Francis Brennan or Corrintra,

Castleblaney, Co. Monaghan.

Many small notes can be found in the reports and margins of

those, mentioning features of the Lockheed P-38 Lightning, which

would have been vastly more advanced than anything fielded by

the Irish Defense forces. Papers in the aircraft even

revealed that it was built at Burbank, California.

The wreckage of the wrecked aircraft was gathered by Irish Army

personnel and sent to Dundalk barracks where it would have been

disposed off.

On the afternoon of December 17th, 1942, a young United States

Army Air Forces pilot took off from Langford Lodge on the edge

of Lough Neagh, en-route to Eglinton near Londonderry.

About 2 hours and 45 minutes later, the pilot, having become

lost and running low on fuel elected that it was time to abandon

the aircraft.

The USAAF Form 14 crash report records the findings of the investigation into the accident:

Pilot took off from AAF Station No. 597 at 1610 hrs with Eglington as destination. He did not have maps or radio contact. Pilot became lost as a result of poor judgement and technique. After flying for about 2 hrs and 45 min his gas became low and it had become dark. The pilot climbed for altitude and jumped about 1900 hrs. The plane crashed in Eire just south of the borderline and about 3 miles NE of Monaghan, Eire. The pilot landed just north of the borderline in Northern Ireland and about 5 miles south of Keady, Northern Ireland.

The plane was a complete wreck and the pilot was unhurt.

90% of the responsibility for the accident rests with the pilot and 10% with Operations at Langford Lodge Air Depot in that they cleared the pilot without a proper map.It is recommended that pilots be impressed with the importance of having all possible aids to navigation in their possession and functioning before attempting X-C flights and that pilots who have had little navigational flying or who use poor judgement and technique in navigation be further trained under close supervision in proper navigational practices.

The pilot of the aircraft also provided a statement for the

enquiry recorded on the Form 14 and that reads as follows:

On 17 December, 1942 I departed from Langford Lodge at approximately 1600 as part of a flight of three P-38s. Due to the congested conditions I was forced to taxi very slowly and to wait for other ships to move and my engines heated enough to light the prestone lights. I took off expecting the engines to cool off right away. I made a wide circle of the field and the engine stayed hot, so I landed at Langford again, taxied off the runway, and shut off the engines. The temperature dropped immediately so I started them again, taxied to the tower and told the inspector, that I was taking off again. After getting a green light I started out for Eglinton from Langford Lodge at a compass heading of 330o which according to the compass card was the correct heading after correcting 5° for wind magnetic variation had already been allowed for.

I had no map as I was supposed to have been following the flight which was lead by a man with a map. My radio was marked out on the form 1-A. Since the weather was reported contact and I expected to reach familiar territory after ten minutes flight I had no doubts about the trip. I flew my compass course, but at the end of ten minutes flying time I began to run into clouds at 1000 feet instead of 1500 as reported for my route home, There were hills to my right higher than any I was supposed to encounter and I recognised them as hills which should have been far to the left of the course I was flying. I made a circle to my left but as I was far off course and had lost sight of the lake I was afraid that the large error in my compass would take me to a place where I would be totally lost. I planned to fly around the hills alter course to the right until I reached the ocean, and then follow the coast to Lock Foyle and on to Eglinton. I attempted to carry out this plan. I reached the coast and flew down the coast. The ceiling over the ocean was about 1200 feet but the clouds were hanging on the tops of the hills. I flew right down the coast looking for the lock but did notice it. I flew into a lock which I recognized as being across the hill from my home station. I went on down the coast but visibility was getting poor. It was then almost 1715 and I knew’ (I thought I knew) that they would be looking for me in another fifteen minutes. I turned on the radio and turned on D channel just in case the transmitter might be working end flew up and down the coast thinking they would plot my course end send help. I throttled back to 200 miles per hour and flew at about 1800 r.p.m. The air was so rought (sic) and I was making some fairly steep turns trying to follow the coast and circling towns that a lower speed did not seem advisable. At 1800 I was still not getting any help and my reserve tanks were dry so I decided to make for England by way of the coast. It was so hazy that I could no longer identify the coast line.

I ran into clouds and rain at about 100 feet so I started back. I saw the lights of a light house and flashed an S.O.S. with my wing lights. I was then hoping for a search light direction. I kept going until I came to two lighted towns close together and knew I was over the Free State. My gas gauge read between ten and fifteen gallons. I knew that unless I got immediate help I was going to have to jump. I headed for North Ireland and climbed through the overcast. The moon was shining above the overcast and as I climbed I saw the overcast start to break up. At 8000 feet I thought I saw lights, but either I was wrong or the clouds again obscured them. I went on to 10,000 feet. My engines were still running but were running on what I figured to be the last five minutes of gas for the tanks were almost empty

I slowed the plane down to 110 miles per hour, throttled back, rolled the stabilizer forward, and held the nose up. I unfastened my safety belt, broke loose the canopy and got my feet on the seat and tried to stand up but the slip stream held me. I grabbed the wheel, steadied the plane and gave another jump. I went up out of the cockpit and over the tail by what seemed to be three or four feet.

I dropped for about 5000 feet I believe because I thought the pack of my chute had broken loose for it was floating in the air beside me. I grabbed for it, realizing (I think now) it to be a futile effort. Then I pulled the ripcord. I received a hard shock as the chute opened and then was floating down. I tried to stop the chute from twisting and then I looked down and passed through the clouds. I saw what I thought to be trees right under and then I hit. I had passed over a hedge - not trees. I gathered up the chute, and an Irishman came running down asking if I was alright. He to1d me I was in North Ireland but my plane had landed in the Free State. His name was “Art Hughes”—his post address “Drum Herney’. I went to his place and was told it was ten after 1900. I had a cup of tea and walked to a rural post office Carna I (sic) which is six miles south of the town of Keady. I tried to call Eglinton but the operator could not get the call through so I called the Keady police. They took me back to Hughes to get my

chute and told me that they had seen my plane. They described it as a total wreck and said it had done no damage except to dig a hole in a pasture. We went to the police barracks in Keady and they contacted the R.A.F. for me who agreed to notify Eglinton and put me in touch with the composite command who sent a car for me.

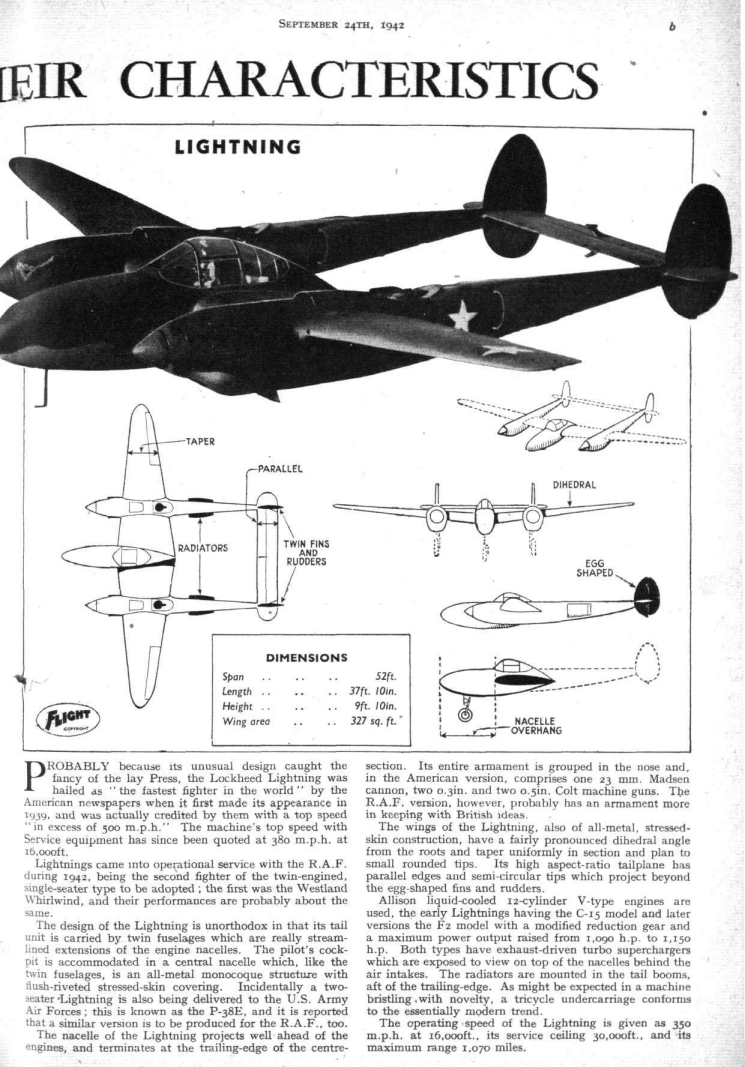

The aircraft was a Lockheed P-38G-5-LO Lighting fighter, one of

the famous twin engine, twin boom fighters produced at the

Burbank Factory in California. The September

24th 1942 edition of the British Flight magazine had

published this specification page on the P-38.

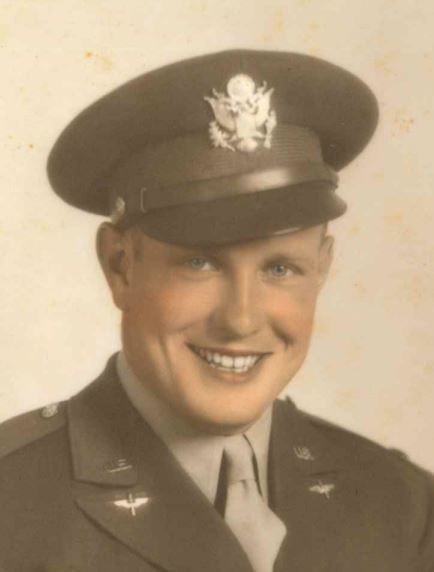

The pilot in this case was the 22 year old 2nd Lieutenant of

the USAAF, Milo E Rundall, O-724562, son of Eva and LeRoy

Rundall from Waterloo in Iowa.

Milo

enlisted as an Army Air Corps officer cadet in September 1941,

and upon completion of flying training was placed on active

service in April of 1942. His local newspaper the Courier

Sun reported on his having completed preliminary flight training

in their 12st December 1941 edition.

Milo

enlisted as an Army Air Corps officer cadet in September 1941,

and upon completion of flying training was placed on active

service in April of 1942. His local newspaper the Courier

Sun reported on his having completed preliminary flight training

in their 12st December 1941 edition.

A few weeks after this, the Waterloo Daily Courier paper carried another short piece about him and included a photo this time.

This had been carried

out at a Gardner Field, California. He then was posted to

Williams Field, Arizona for advanced training. The newspaper of

5th May 1942 recorded his having been awarded his silver wings

badge and commision as an officer that week at the Arizona base

upon completion of training. He was transferred overseas

in September 1942, coinciding with the transfer of the 82nd

Fighter Group to Europe. They sailed to Europe without

their aircraft and were only assigned with new aircraft from

assembled aircraft from November onward.

This had been carried

out at a Gardner Field, California. He then was posted to

Williams Field, Arizona for advanced training. The newspaper of

5th May 1942 recorded his having been awarded his silver wings

badge and commision as an officer that week at the Arizona base

upon completion of training. He was transferred overseas

in September 1942, coinciding with the transfer of the 82nd

Fighter Group to Europe. They sailed to Europe without

their aircraft and were only assigned with new aircraft from

assembled aircraft from November onward.

The day before the incident with aircraft 42-12814, a large

part of the fighter group was flew enmasse to Cornwall enroute

to North Africa in the follow up the the allied landings in

North Africa, Operation Torch. Milo Rundall and the

remainder of the group flew in the following days.

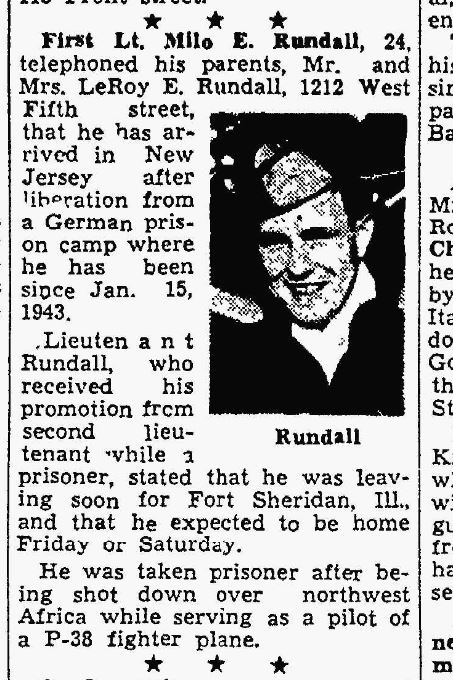

Milo fought for about a fortnight in North Africa until he was

shot down on the 15th January 1943 and made a prisoner of

war. As detailed in the book, A

History of the Mediterranean Air War, 1940–1945, Volume 3,

Milo and his squadron, the 96th Fighter Squadron of the 82nd

Fighter Group was flying as escort to a B-26 Marauder raid when

they were intercepted by Luftwaffe fighters, resulting, among

other losses, in the shooting down of 2/Lt Rundall and his

Squadron mate 2nd/Lt Raymond M Black. Both men were taken

as prisoner of war, but 2nd/Lt Black also died on the same

day. The news of Milo's loss was relaid to his parents at

the end of January 1943 and the following day reported in the

local newspaper. Reports in the newspaper trickle off

somewhat after this, but in March 1945 a letter was received by

his parents from Milo. In this he mentioned that he was

continuing his studies of journalism and philosophy under

facilities provided by the Red Cross. HE was being held at

that time in Stalag Luft III.

It would be June 1945 before his parents would have the glad news that he was back in the united States and, as always, the Courier reported this also.

Milo returned to his parents and reenlisted in the Air Force in

November 1945, then the following January married Norma

Olson. He finally was honorable discharged from the forces

in May 1946.

He passed away in Cedar Falls on the 13 March 2006.

In 2019, the Monaghan Spitfire group in conjunction with Queens

University Belfast and County Monaghan Museum carried out an

excavation of the crash site of P-38 42-12814. This

resulted in a great deal of publicity for the activity and all

major Irish news outlets carried the story.

Since the excavation, the findings have been added to the

exhibition running in Monaghan County Museum along side those

found from Spitfire R6992 in

2018. Parts have also been provided for display to City of

Derry Airport.

This link on the Irish Times website contains one of the

better summary of events carried out. The organizers of

the excavation sadly no longer correspond with my website for

unknown reasons.

The recovered parts are displayed at the County Museum from

2019 following their cleaning and conservation.

This exhibition opened in June 2018 and information about it can

be found here on the Museum website.

Compiled 2019 by Dennis Burke, sourced from Irish Army files

G2/X/USAAF Crash File 43/12/17/502; Fork-Tails over Ireland, M.

Gleeson, Flypast Sep. 2000; 82ndfightergroup.com, Monaghan

Spitfire and Monaghan County Museum facebook pages, Jonny McNee,

2017, newspapers.com, ancestry.com various databases.