Landings at Leopardstown Racecourse,

Dublin, May 1941

In the short history of foreign aircraft landings in neutral

Ireland during the 1939 - 1945 period, apart from the airfields

at Gormanstown, Baldonnel, Rinneanna and Collinstown, not many

places would see multiple landings of foreign aircraft.

The Marsh in Skibbereen, Cork, would see two bomber landings in

the space of two months in 1944 and the the subject of this

page, Leopardstown Race Course and its surroundings would

receive two aircraft, one British in May 1941 and an American in

February 1944.

The first of these landings took place next to Leopardstown

racecourse itself, in the townland of Ballyogan, which lies to

the south of the race course track. The Irish newspapers

on May 23, 1941 carried the very subdued report that: The Government Information Bureau last night

stated: A British aircraft crashed this afternoon in

County Dublin. The crew, who were uninjured, have been

interned. This was reported alongside

reports of the fighting on the island of Crete.

The previous afternoon had seen the dramatic arrival of a twin engined Royal Air Force fighter aircraft, one of the still relatively new Bristol Beaufighter aircraft. The Irish Military Archives File G2/X/0744 records that the aircraft arrived at 17:40 hours on the Thursday evening in a field 'adjoining Leopardstown'. It had been observed entering Irish airspace some miles south of Dalkey, then circled around above Blackrock and Bray before making its landing. The Army noted that the owner of the field, which was sown with wheat was one Joseph McGrath of the Irish Hospital's Trust. Two days after the landing, its was reported that due to damage to the field and crop, compensation for the owner might be required. On board the aircraft were two RAF officers and a Sergeant.

A report from the local Garda, the Irish Police force, recorded how a passing lorry driver had reported to Stepaside Police station that an aircraft was on the ground. An officer arriving at the scene had to stop the crew members from destroying equipment on the aircraft. Shortly thereafter, members of the Local Security Force (LSF), a wartime force set up to assist the Garda during this time of emergency, had to be used to keep the growing crowds of civilians back from the aircraft. It is said that people wanted the crew to join them for 'refreshments'. They were finally brought to the LSF post at Foxrock and given refreshments by members of the group. When met by the military, they had been given calling cards by LDF member William Murphy, in whose house at St. Marys, Westminster Rod, Foxrock, they had been taken. Later again they were taken to Cabinteely Garda Station and thence to Portobello Barracks. They were interrogated there, and said to be friendly, but uncommunicative. They were concerned about the security of their aircraft.

They reported that they were part of a flight of four aircraft

flying from Gibraltar to the UK, and had run out of fuel due to

loss of bearings and failure of their wireless equipment.

A large amount of documentation found in the aircraft also

indicated clearly where they were coming from.

Their names were recorded in the report in a number places but

in general on the first day they were understood to be:

F/O H C Verity 72507 Sydenham, Bisley

St, Strand, Gloucester

F/O J B Holgate, 33426, 113 Shirley Way, Croyden,

Surrey

Sgt Barnett, W, 973926, Main St, Grosssgates,

Dunfermline

Given the procedures being followed by the Irish government at

that time, it was determined that they must be interned as

belligerents and found themselves in short order being driven to

the Curragh Camp in Kildare.

Their aircraft was largely intact, and its identity could be

read from the rear fuselage as serial number T3235. And, a

photo of the aircraft exists in the field, presented below with

the kind help of A. Flanaghan.

One can see the serial number T3235 on the rear fuselage along

with the partially obscured squadron markings of ?N-H.

This was a Beaufighter IC, the long range heavy fighter version

for Coastal Command use. The aircraft was dismantled and

removed from the site to Baldonnel by an Irish Air Corps

team.

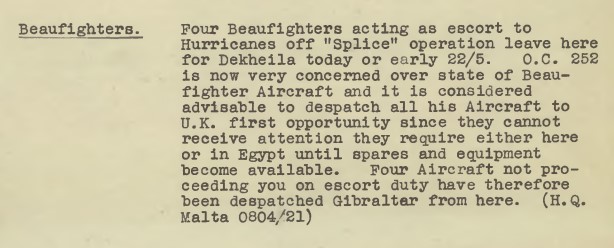

It was an aircraft operated by 252 Squadron, Royal Air

Force. They were based at RAF Aldergrove in Northern

Ireland but a detachment of 15 aircraft were deployed to the

Mediterranean to operate from Malta at the start of the month to

help defend the island against Axis attacks. Bombing raids

on the Squadron had resulted in the need to fly four damaged

Beaufighters back to the UK for repairs. The situation was

important enough to make it into the Admiralty War Diary for the

21st of May 1941.

The 252 Squadron Operations Record Book for this date records

that four Beaufighters from the detachment had undertaken the

flight from Malta to Gibraltar. While Verity's aircraft

ended up in Ireland, another crash landed in the sea off Mounts

Bay and were rescued by a small coastal vessel. The

remaining two aircraft landed in Cornwall and Somerset.

Weather in both Northern Ireland and South West England was

reported bad on the day.

Using a combination of modern day records and the accumulated

research of others over a 40 year period, the story of the crew

becomes known.

The pilot of

the aircraft was non other than the soon to be famous Hugh

Beresford Verity.

The pilot of

the aircraft was non other than the soon to be famous Hugh

Beresford Verity.

The British Military Attache in Dublin, Lywood, sent a

telegram, now recorded in the events AIR81 file in the UK

National Archives, to the Air Ministry and RAF Northern Ireland

with the following report from F/O Verity.

Report of F/O Verity Pilot of

Beaufighter No.T3235 (PNM) which force landed in Eire on

22/5 is as follows.

Airborne Gibraltar 0905 GMT. Last fix Cape Carvoiero.

Finisterre obscured by cloud. Wireless receiver found

unserviceable at 1400 hours. Visibility and height of cloud

zero-zero at 1435 G.M.T. E.T.A. Land’s End. Climbed

above cloud to 6,000 ft. and searched for gaps in

cloud and land. Transmitted messages to St.Eval

about (OMR) movements and left I.F.F. on Stud 3.

Petrol exhausted after 7 hours 25 minutes in the air. Forced

to land Fox Rock, Dublin at 1630 G.M.T. Undercarriage and

port engine and starboard aircrew badly damaged. Destroyed

I.F.F. charts with co-ordinates torn up and some fragments

left in aircraft and other fragments and C.D.75 taken by

Military Intelligence of Eire. Report Ends.

As result of my previous representation to Director

of Eire Intelligence I consider documents taken over

by them are in safe custody.

F/O Verity upon his escape reported for duty with 54

Operational Training Unit (OTU) on the 27 July 1941 and there

after to 29 Squadron.

His family provided a copy of a memoir chapter that he

prepared, and his description of the arrival in Ireland is as

follows:

So we four crews and our passengers

found ourselves in Gibraltar being briefed on the morning of

Thursday 22 May, 1941. It seemed that the weather

would be cloudy and then clearer. I asked Sergeant

Barnett to plan a flight where we could let down through

cloud, if need be, to sea level fifty miles southwest of

Land's End. When we could see the sea, in very poor

visibility, there was a coast-line to the East but it was

not Land's End. We were near a small ship called the

François Xavier with no national colours. We circled

it and John tried to make contact in Morse flashing an

Aldiss lamp. We could not decide where we were, as the

poor meteorologists in Gibraltar had very sketchy

information to base a forecast on, and had probably given us

very misleading forecast winds.

As the weather closed in down to sea

level I pressed on north climbing up through the cloud and

rain. The next sight of land was trees and hedges

going by in the clouds at 1,500 feet indicated. I

thought that there could be Welsh mountains ahead and

climbed up higher. Then I resolved not to go down to

sea level again until I could see a clear way down. I

think I must have flown down the top slope of a front before

I could see the sea again. Ahead was a coastline and I

thought that I might just have enough fuel to reach it

before my tanks ran dry.

Inland there was a racecourse which I

thought might do for a forced landing but it was obstructed

by tripods of pine trees. So I managed to glide, all

fuel gone, to belly-land in a field beyond. A girl ran

up to us. ‘Where are we?’ I asked. ‘Sure you are

in Eire,’ she said.

What an amateur aviator I was!

Could not find England!

There was poor old H Hugo on her belly

not far from the concrete wall whose top we had dented,

surrounded by friendly and curious local people.

Sergeant Barnett and I heard a small explosion from the

Beaufighter and saw a puff of smoke. It was only John

Holgate, my passenger, blowing up the secret IFF

(Identification Friend or Foe radar responder). It

had not occurred to me to do it.

Out of the little crowd emerged a

charming doctor. He noticed my bleeding forehead where

it had set forward against the glass reflector plate of my

gun sight. He persuaded the Army and Garda that he had

to dress the wound in his house ‑ and give us, all three,

cups of tea. He secretly took my logbook and diary to

deliver to the British Office in Dublin. He

anticipated the inevitable ‘missing’ telegram with his own

good news to Bisley. To avoid getting him into

trouble, I have forgotten his name, but I never cease to be

grateful.

F/O Verity, was

interned with the others but he and Holgate seized the

chance to escape during the Derby Day escape, with four

other RAF men, on 25 June 1941. His son, Richard had

been born during his time interned when he was appointed

senior British officer in the British internee group.

Following his escape, he wrote to Colonel Thomas McNally,

the Camp commander to thank him for his and his men's

conduct during his time interned.

The Sunday Mirror

on 21 November 1976, carried a two page spread, entitled,

the Cushiest Prison Camp of the War, telling his

story of his fives weeks interned in Ireland.

Hugh's later wartime exploits were written about in his book, We Landed by Moonlight, published first in 1978. It told of the missions he is beset known for, flights into occupied Europe in Lysander aircraft, dropping and collecting agents working with the resistance movements in German occupied areas.

Hugh passed away in November 2001 and his obituary featured in

the Telegraph newspaper.

The Radio

Operator/Observer on the aircraft, seated at the rear canopy,

was Sgt William Barnett 973926.

The Radio

Operator/Observer on the aircraft, seated at the rear canopy,

was Sgt William Barnett 973926.

William was born in Dunferline on 8 January 1917, the son of

XXX and XXX. His parents resided at Burnside Terrace,

Crossgates, Fifeshire during the war.

He was interned in the Curragh internment camp until October

1943 when he was released along with another batch of airmen

what the Irish government agreed were not on combat missions at

the time of their internment. Upon his release he filed a

short escape and evasion report that recorded his previous two

years:

Internment: I was a member of the crew

of Beaufighter which took off from Gibralter on 22 May 1941

and came down on the same day at LEOPARDSTOWN, CO.

DUBLIN. I was thereafter interned in THE CURRAGH Camp.

Following his return from internment, he spent a period

assigned to RAF 45 Group, sailing on the Ile de France arriving

in New York on the 7 September 1944 and was crewed on Liberator

KH353 being delivered from Montreal to the UK over the 9th/10th

November 1944, returning to Montreal as a passenger on Liberator

AL592 on 23rd November 1944. His Ferry Card has an

annotation noting that he had been part of Course 14 of 105

Operational Training Unit.

At some point in the weeks following that, William found

himself the victim of a dangerous aircraft accident what would

see him display a great act of bravery.

CENTRAL CHANCERY OF THE ORDERS

OF KNIGHTHOOD.

St. James's Palace, S.W.1

27th April, 1945.

The KING has been graciously pleased to give orders

for the following appointment to the Most Excellent Order of

the British Empire and the following awards of the George

Medal and the British Empire Medal:—

To be an Additional Member of the Military

Division of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire:—

Warrant Officer William BARNETT - (973926).

Royal Air Force.

Awarded the British Empire Medal (Military

Division).

1521658 Flight-Sergeant Matthew ANDERSON,

Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve

In December, 1944, a Mitchell aircraft, which

was fully loaded with petrol, caught fire soon after the

take-off. The pilot, Flight Sergeant Anderson, made a crash

landing during which he and the navigator, Warrant Officer

Barnett, received head and other superficial injuries, burns

and shock. They both left the wrecked aircraft by way of the

escape hatch and then returned to rescue the radio operator

who was trapped in the flames beneath the fuselage. Warrant

Officer Barnett, using great strength, lifted the rear

portion of the fuselage whilst Flight Sergeant Anderson

crawled in and dragged the radio operator clear. They then

assisted him away from the conflagration. They showed

disregard for their own safety and injuries and, by their

courage, undoubtedly saved the life of their comrade.

It seems likely that the aircraft involved was Mitchell KJ722

which has a circumstances of loss of: Wrecked when crashlanded 4 mi N of

Dorval, Canada Dec 7, 1944 after catching fire in air.

The Ottowa Journal on the evening of 7th December 1944

reported:

CRASH AT CARTIERVILLE. MONTREAL Dec 7. (CP) A twin-engine aircraft

crashed in a field near suburban Cartierville today soon

after taking off from Dorval Airport The three occupants of

the 'plane escaped with slight bruises.

The following day, The Gazette, from Montreal carried the

following article.

2 Fliers Save Comrade In Crash

Landing Here

Two men risked their lives to save a third, when an

aircraft of the R.A F. Transport Command was forced to land

between Cartierville and St. Laurent yesterday morning. It

is not known how the aircraft caught fire, but a witness, E.

Grou, a farmer of St. Laurent said he saw the fire when the

plane was over his farm and expected It to explode when it

hit the ground. He saw the pilot and navigator crawl out

safely and then return to drag out the radio operator who

was unable to extricate himself. all non-commissioned

officers of the R.A.F.T.C., had taken off from Dorval

airport only a few minutes previously on a routine flight.

R.A.F.T.C. officials said the men suffered superficial

burns, but were otherwise unhurt. The aircraft, a Mitchell

twin-engine bomber was completely destroyed. Rescue

operations were hindered for some time owing to the thick

snow, but with the aid of J. Lecavalier. S. Sgt Walter E.

Plaine was able to render first aid.

William Barnett

passed away in Bristol in 1992, having married in 1949.

The

passenger being carried on T3235 was F/O John Basil Holgate,

33426, another pilot from 252 Squadron. He was born

in 1919 to Gladys and Basil Holgate in Southend on Sea.

The

passenger being carried on T3235 was F/O John Basil Holgate,

33426, another pilot from 252 Squadron. He was born

in 1919 to Gladys and Basil Holgate in Southend on Sea.

John was commishioned into the RAF in the summer and August of 1939. He was posted it appears first to 217 Squadron flying Avro Anson's with Coastal Command from February 1940. It was with them that he suffered a forced landing at sea on 21 November 1940. John and his crew of three had to come down in the sea off Kelland Head on the north coast of Cornwall flying in Anson R9701. The four were picked up by a passing British trawler.

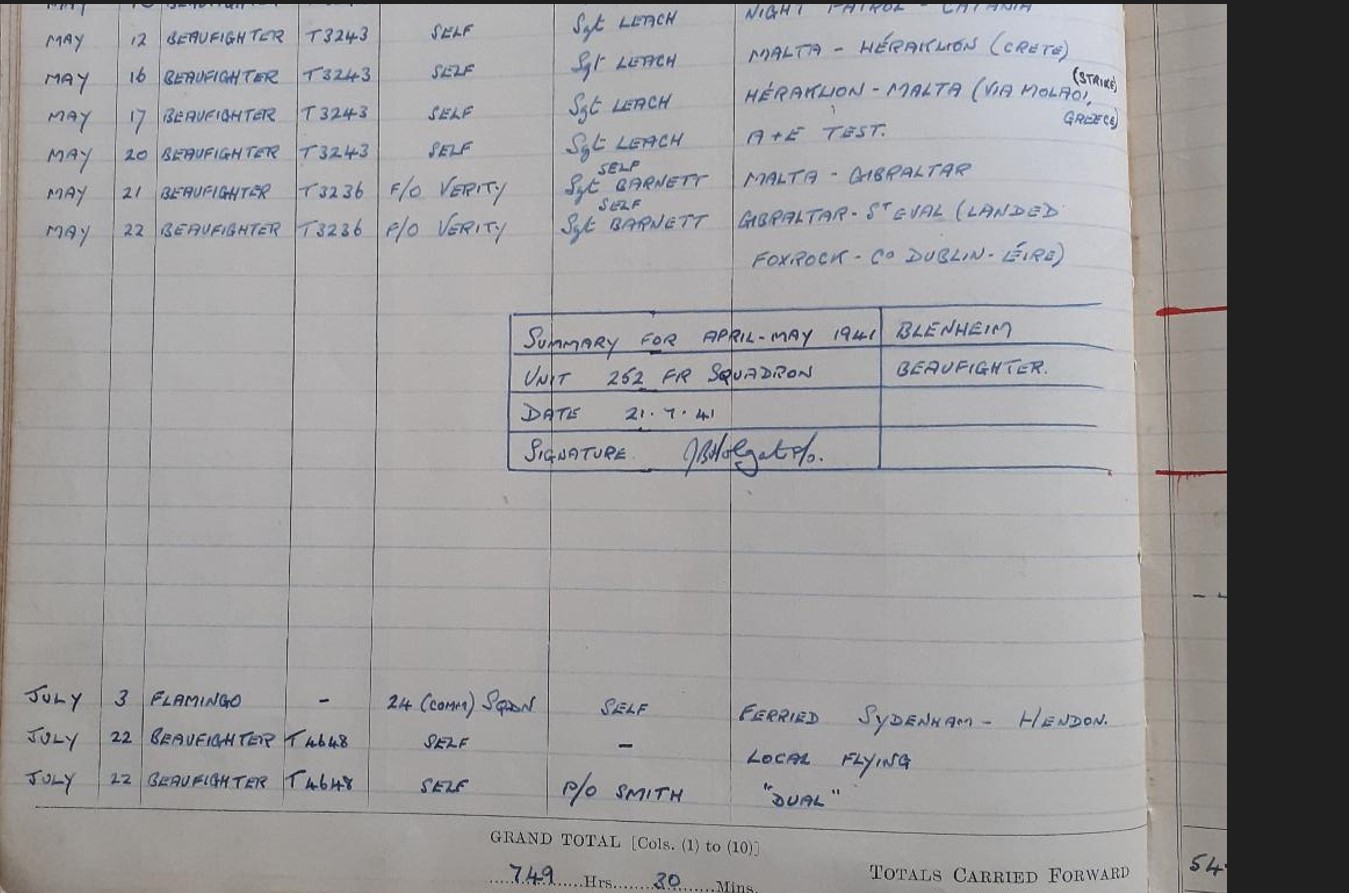

John's family were so kind as to send a scan of the page of his flying log book recording his arrival in neutral Ireland. The serial number of the aircraft doesn't match most records from the time but only misses out by a digit. It is interesting to note that he had flown a strike mission only four days before hand in Greece which had only days before been captured by German forces.

Also of note is his return flight from Belfast after his escape

from internment during the Derby Day Breakout.

After his escape from internment, he was in 1942 posted to 143

Squadron then flying as a non operational, Operational Training

Unit using Blenheims. They then transitioned to

Beaufighters and it was while flying these that he was awarded

the Distinguished Flying Cross for, as the RAF publicity press

release mentioned: Squadron Leader

Holgate, now on his second tour of operational duty, has

displayed the greatest enthusiasm and keenness to engage the

enemy. As a flight commander he has shown both courage and

determination and conscientious devotion to duty at all

times.

He continued to serve in the RAF post war and in 1952 was

awarded an Air Force Cross.

He passed away on 13th January 1983 in Buckinghamshire with a

short death notice published in The Times newspaper.

Compiled by Dennis Burke, 2024, Dublin and Sligo. With

the very kind assistance of the Verity family and from Holgate

family.